Today, the Nobel Prize winners in the field of medicine were announced. All three winners are esteemed scientists who have discovered “therapies that have revolutionized the treatment of some of the most devastating parasitic diseases”, according to the Nobel committee. This is doubtlessly true: two of the winners’ discoveries have led to the development of a drug that has nearly brought an end to river blindness; the third scientist developed a drug that has reduced mortality from malaria by 30 percent in children, and saves over 100,000 lives each year.

I could go on about the myriad of ways in which medicine is improving the human condition worldwide, or about how we’re eradicating some diseases that have inflicted the human race since times unknown. I won’t do that. The progress of medicine is self-evident, and in any case is a matter for a longer blog post. Instead, let us focus on a different venture: the attempt to forecast the Nobel Prize winners.

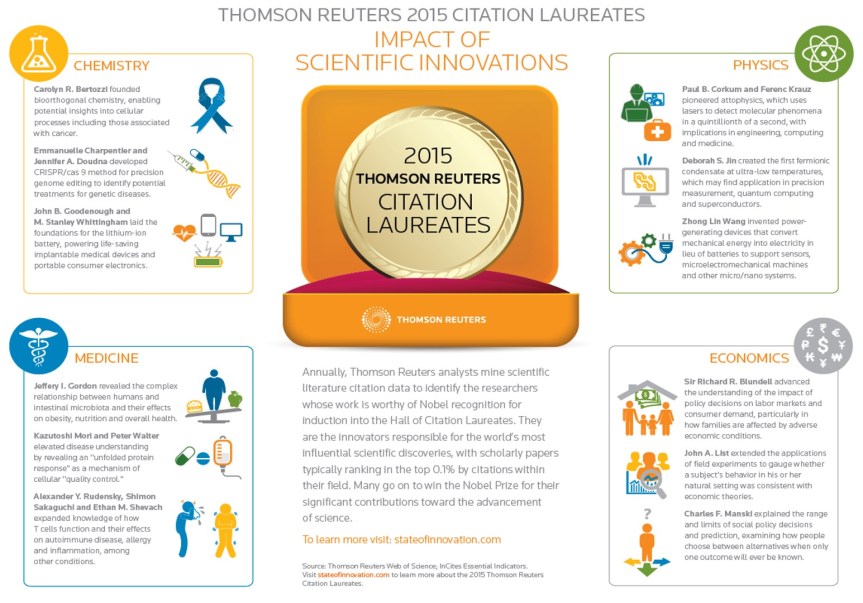

The Citation Laureates

Every year since 2002, the Thomson Reuters media and information corporation makes a shot at forecasting the Nobel laureates. To that end, they analyze the most highly cited research papers in every field, and the authors behind them. One’s prestige as a scientist largely comes from high citation rate – i.e. the number of times people have referred to your work when conducting their own research. It’s therefore clear why this single simple parameter, so easily quantified, could serve as a good base for forecasting the annual Nobel winners.

So far, it looks like Thomson Reuters have done quite well with their forecasts. In every year except 2004, they have successfully identified at least one Nobel Prize winner in all the scientific fields: Physiology or Medicine, Physics, Chemistry and Economics. Overall, Thomson Reuters has “correctly forecast 21 of 52 science Nobel Prizes awarded over the last 13 years”.

It is fascinating for me that by working with tools for the analysis of big data, one could reach such a high rate of success in forecasting the decisions made by the Nobel committees. But here’s the deeper issue, in my opinion: Thomson Reuters clearly intends only to forecast the Nobel winners – but is it possible that their selection is more accurate than that of the Nobel committee?

The Limits of Committees

How is the Nobel Prize decided? Every year, thousands of distinguished professors from around the world are asked to nominate colleagues who deserve the prize. Each committee for the scientific prizes ends up with 250-350 nominees, whom they then screen and analyze in order to come up with only a few recommendations that will be presented to the 615 members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences – and they will vote for the final winners.

Note that the rate-limiting step in the process is contained in the hands of the committee members. The number of members changes between each committee, but generally ranges between 6 and 8 members in each committee. And as anyone who has ever taken part of any committee discussion knows, there are usually only two or three people who really influence and shape the debate. In other words, if you want to have a real chance at winning the Nobel Prize in your field, you had best develop your connections with the most influential members of the appropriate committee.

Please note that I’m not accusing the Nobel committees of fraud or nepotism. However, we know that even the best and most reliable experts in the world are subject to human biases – sometimes without even realizing that. The human mind, after all, is a strangely convoluted place, with most of the decision making process being handled subconsciously. Individual decision makers are therefore biased by nature, as are small committees. The Nobel Laureates selection process, therefore, is biased – which I guess we all know anyway – and even worse, it remains under wraps, and the actual discussions taking place are not shared by the public for criticism.

Examples for (alleged) bias can be found easily (heck, there’s an entire Wikipedia page dedicated to the subject). Henry Eyring allegedly failed to receive the Nobel Prize because of his Mormon faith; Paul Krugman received the prize because of (again, allegedly) left-leaning bias of the committee; and when the scientist behind HPV discovery was selected to receive the prize, an anticorruption investigation followed soon after since two senior figures on the committee had strong links with a pharmaceutical company dealing with HPV vaccines.

The Wisdom of Data

Now consider the core of the Thomson Reuters process. The company’s analysts go over all the papers and citations in an automated fashion, conducted by algorithms that they define. The algorithms are only biased if they’re created that way – which means that the algorithms and the entire process will need to be fully transparent. The algorithms can cut down the list of potential candidates into a mere dozen or so – and then allow the Royal Swedish Academy do the rest of the work and vote for the top ones.

Is this process necessarily better than the committee? Obviously, many flaws still abound. The automated process could put more emphasis on charismatic ‘rock stars’ of the scientific world, for example, and neglect the more down-to-earth scientists. Or it could focus on those scientists who are incredibly well-connected and who have many collaborations, while leaving aside those scientists who only made one big impact in their field. However, proper programming of the algorithms – and accurately defining the parameters and factors behind the selection process – should take care of these issues.

Does this process, in which an automated algorithm picks a human winner, seems weird to you? It shouldn’t, because it’s happening on the World Wide Web every second. Each time you’re doing a Google search, the computer goes over millions of possible results and only shows you the ‘winners’ at the top, according to factors that include their links to each other (i.e. number of citations), the reputation of the site, and other parameters. Google has brought this selection process down to a form of art – and an accurate science.

Why not do that to the Nobel Prize as well?

.

.

.

Your Nobel Forecast

Over the next week, the recipients of the Nobel Prize will be announced one after the other. Would you like to impress your friends by forecasting the recipients? Here’s an infographic made by Thomson Reuters and detailing their forecasts for 2015. Good luck to everyone in it!

Originally from Thomson Reuters.

Credit: the Nobel Prize medal's image at the top of the post was taken by Adam Baker on Flickr.